Hyderabad's forgotten waterscapes

Hyderabad’s water bodies hold a complex and fascinating history. What many residents now call “lakes” are, in fact, man-made “tanks,” engineered decades ago for drinking water and agrarian purposes. The Deccan Plateau—where Hyderabad is located—has uneven terrain, causing water to run off in multiple directions and accumulate at various points. Rainwater from within the GHMC area eventually drains into both the Godavari and Krishna rivers.

This geography led to the construction of a vast, interconnected system of tanks, linked across different contour levels. This planning and engineering ensured a reliable water supply for residents and small-scale agriculture, even during low-monsoon years, while also supporting irrigation.

Today, many of these tanks have been reduced to cesspools due to the unchecked inflow of sewage and municipal solid waste. In the name of “protection” and preventing encroachment, ring bunds—often used as roads or tank bunds—have been built as rigid boundaries. If you can walk around a lake without any obstructions, it often means its natural extent has been altered. A live, shifting edge that changed with the seasons has been replaced with a hard line, damaging the ecological function of the shoreline. The water levels in such tanks now remain fixed year-round, instead of responding naturally to rainfall and seasonal change.

Hussain Sagar, for example, lost its wetlands when Necklace Road was built across its full-tank level. Over time, the transformation of these tanks has also erased their original, culturally rich names—many tied to individuals, castes, activities, or local folklore—replacing them with new names that obscure both their cultural and engineering heritage.

While remote-sensing analysis may suggest an increase in water surface area, these are often not functioning ecosystems but stagnant cesspools. What was once engineered to supply drinking water and support irrigation has become a source of flooding. What was designed to hold water and recharge groundwater is now filled, plotted, and converted into built-up areas.

These tanks may not have been “natural” in the strictest sense, but they were part of a well-thought-out water management system. Ironically, despite having better technology today, we have degraded what earlier generations built with less. While we no longer rely on these tanks for our water supply, their continued “utility” must be questioned. Without carefully removing the bunds—many of which now double as roads—they will continue to trap water in the wrong way. Meanwhile, construction has spread into areas never meant for permanent structures, with little regard for careful design or hydrological logic.

To understand these hidden waterscapes—the interconnected tank network, water flows, and vanished structures—we bring together data on terrain, tanks, watershed boundaries, natural drainage patterns, and archival maps.

We have also incorporated recent rainfall events recorded across nearly 150 automatic weather stations (as reported by TGDPS) and the water stagnation points identified by GHMC.

As you follow these drainage networks, you can trace the links between various tanks in the city across contour lines. Each AWS station records rainfall in its respective catchment, indicating which tanks are likely to receive runoff downstream.

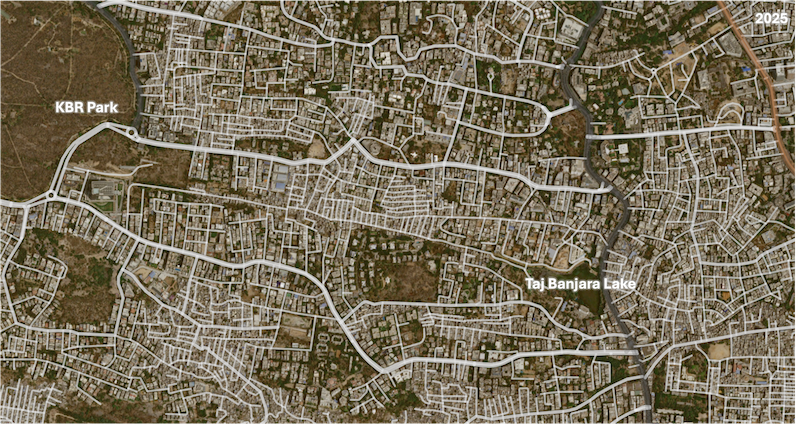

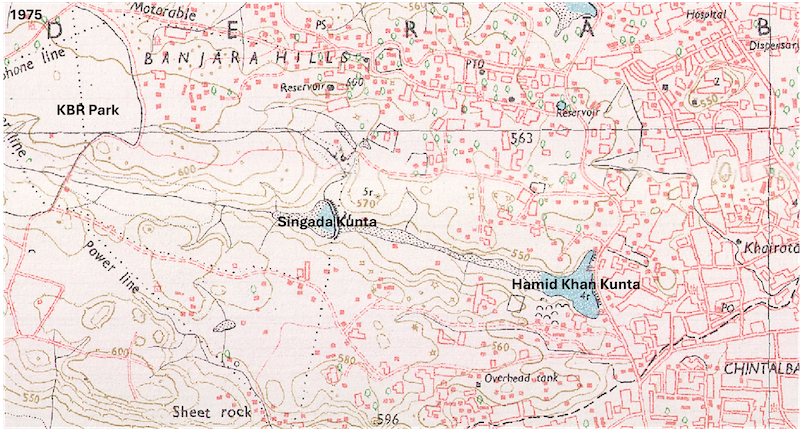

Below are some examples—slide through to see the changes over time. The interactive map at the end of the page allows you to explore maps dating back to 1854. We will continue updating these with more maps and stories.

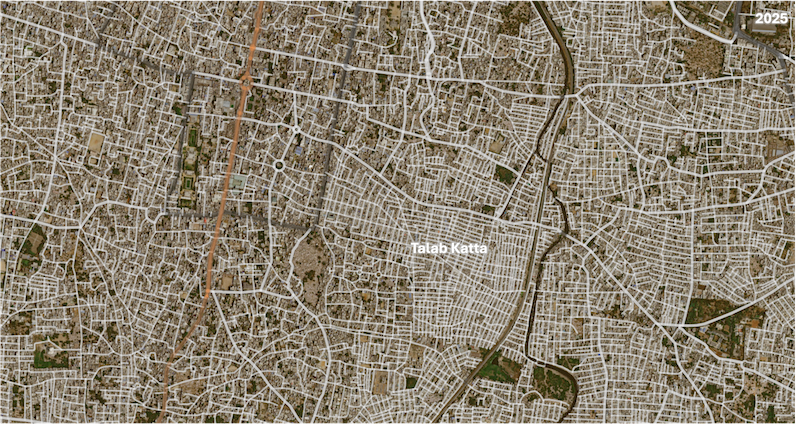

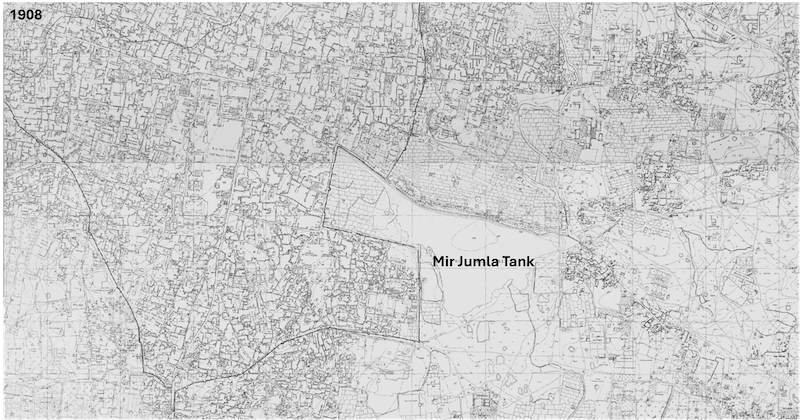

Mir Jumla Tank (Talab Katta)

This tank, named after the commander of Golconda, once existed near Mir Momin's tomb. While the tank itself is now gone, its memory persists in the area's name, Talab Katta, meaning "tank bund".

Singada Kunta

This tank, named after the water chestnut (singada), is an example of complete loss. It has been "completely turned into a slum" with its connecting blue line (a water channel from KBR Park to Taj Banjara Lake covered by an RCC slab. Taj Banjara Lake Originally known as Hamid Khan Kunta, the tank now faces severe pollution from sewage and municipal solid waste.

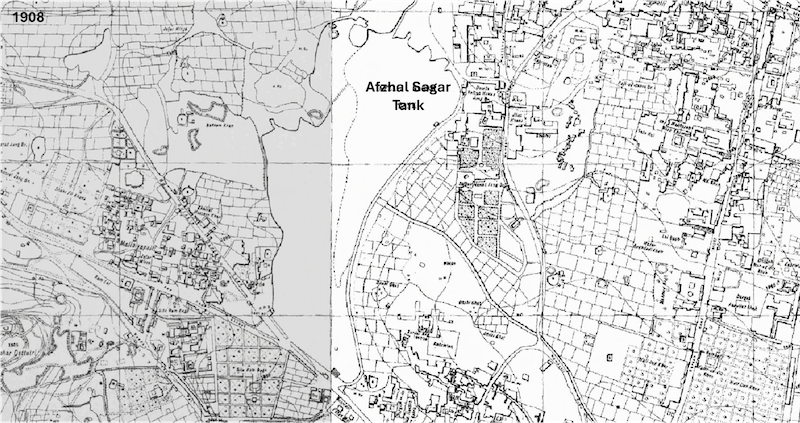

Afzal Sagar

This large tank, located behind Nampally railway station, has a dramatic story linked to the memory of the 1908 Musi River flood. After a 1970 flood scare, the tank was completely breached, leading to the development of a huge colony known as Afzal Sagar. The presence of a Katta Maisamma temple nearby (Katta means "bund" in Telugu, and Maisamma is the goddess who supervises the bund) serves as a physical reminder of the tank's former existence and purpose. Many tanks across Hyderabad have such temples, symbolizing their historical significance and the goddess's role in regulating water flow.